Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

Content Oriented Web

Make great presentations, longreads, and landing pages, as well as photo stories, blogs, lookbooks, and all other kinds of content oriented projects.

EXHIBITION PROJECT

HOUSE OF SPIRIT

EXHIBITION PROJECT

HOUSE OF SPIRIT

A place for discussion, reflection and hope

A place for discussion, reflection and hope

"The House of Spirit" is a remarkable collection featuring some of the rarest ancient icons, relics, illuminated manuscripts, and carefully curated contemporary paintings. This collection serves as a conceptual bridge, connecting the worlds of post-Byzantine and Medieval art to the realm of Fine art in the 21st century.

At the heart of The House of Spirit lies a treasure trove of exquisite and precious artefacts, carefully brought together over years of masterful selection. These remarkable objects represent the pinnacle of artistic achievement in their respective genres.

The profound concept of The House of Spirit transcends the boundaries of specific religious traditions. It serves as an expansive platform for exploring the realm of spirit and faith, inviting people to reflect on their beliefs and their place in the universe, enhancing a sense of unity and shared understanding among diverse individuals.

The intentional juxtapositions in The House of Spirit exhibition spark an array of historical involves and cultural studies. Each artefact becomes a catalyst for dialogue, encouraging creative discussions and fostering moments of deep introspection.

At the heart of The House of Spirit lies a treasure trove of exquisite and precious artefacts, carefully brought together over years of masterful selection. These remarkable objects represent the pinnacle of artistic achievement in their respective genres.

The profound concept of The House of Spirit transcends the boundaries of specific religious traditions. It serves as an expansive platform for exploring the realm of spirit and faith, inviting people to reflect on their beliefs and their place in the universe, enhancing a sense of unity and shared understanding among diverse individuals.

The intentional juxtapositions in The House of Spirit exhibition spark an array of historical involves and cultural studies. Each artefact becomes a catalyst for dialogue, encouraging creative discussions and fostering moments of deep introspection.

"The House of Spirit" is a remarkable collection featuring some of the rarest ancient icons, relics, illuminated manuscripts, and carefully curated contemporary paintings. This collection serves as a conceptual bridge, connecting the worlds of post-Byzantine and Medieval art to the realm of Fine art in the 21st century.

At the heart of The House of Spirit lies a treasure trove of exquisite and precious artefacts, carefully brought together over years of masterful selection. These remarkable objects represent the pinnacle of artistic achievement in their respective genres.

The profound concept of The House of Spirit transcends the boundaries of specific religious traditions. It serves as an expansive platform for exploring the realm of spirit and faith, inviting people to reflect on their beliefs and their place in the universe, enhancing a sense of unity and shared understanding among diverse individuals.

The intentional juxtapositions in The House of Spirit exhibition spark an array of historical involves and cultural studies. Each artefact becomes a catalyst for dialogue, encouraging creative discussions and fostering moments of deep introspection.

At the heart of The House of Spirit lies a treasure trove of exquisite and precious artefacts, carefully brought together over years of masterful selection. These remarkable objects represent the pinnacle of artistic achievement in their respective genres.

The profound concept of The House of Spirit transcends the boundaries of specific religious traditions. It serves as an expansive platform for exploring the realm of spirit and faith, inviting people to reflect on their beliefs and their place in the universe, enhancing a sense of unity and shared understanding among diverse individuals.

The intentional juxtapositions in The House of Spirit exhibition spark an array of historical involves and cultural studies. Each artefact becomes a catalyst for dialogue, encouraging creative discussions and fostering moments of deep introspection.

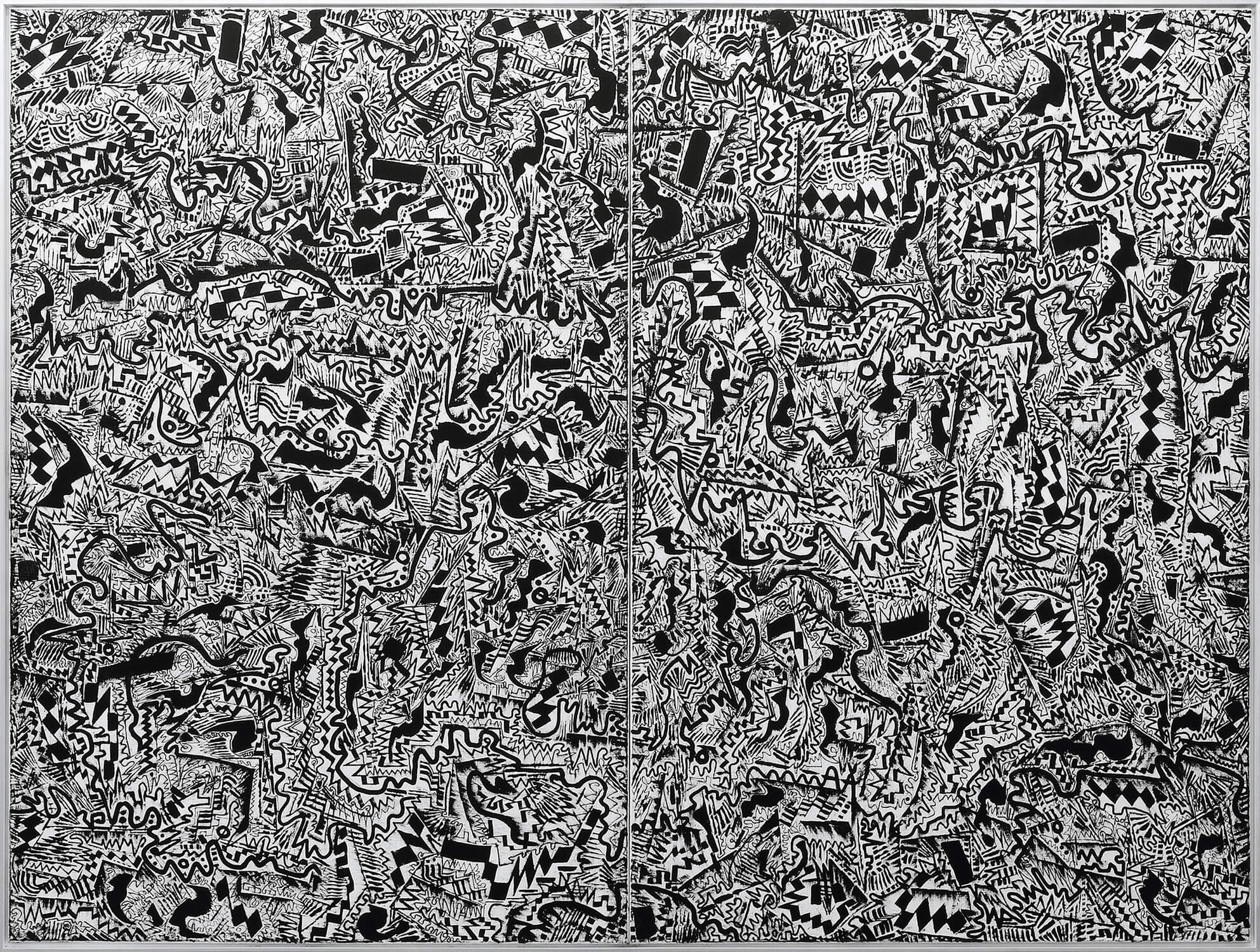

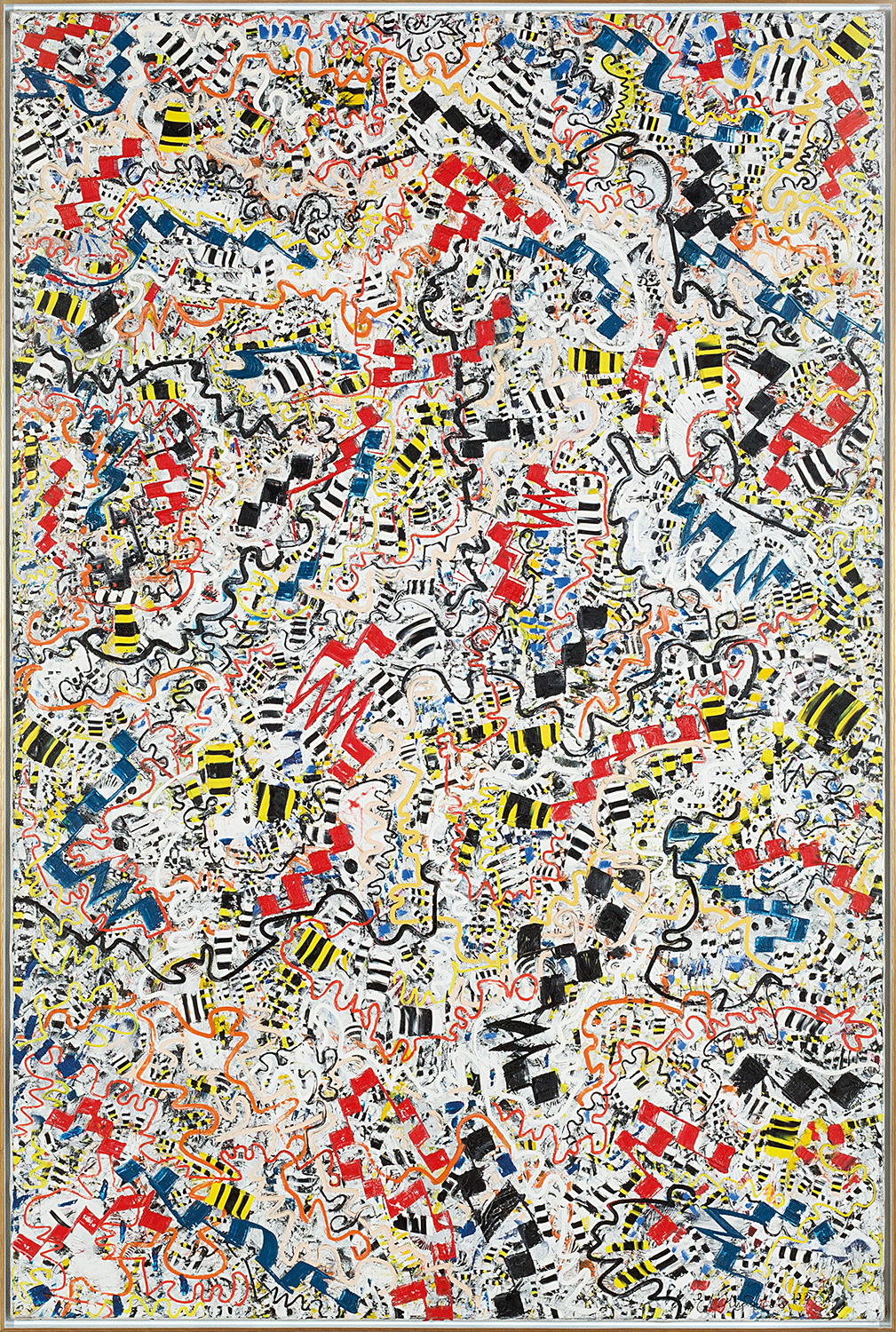

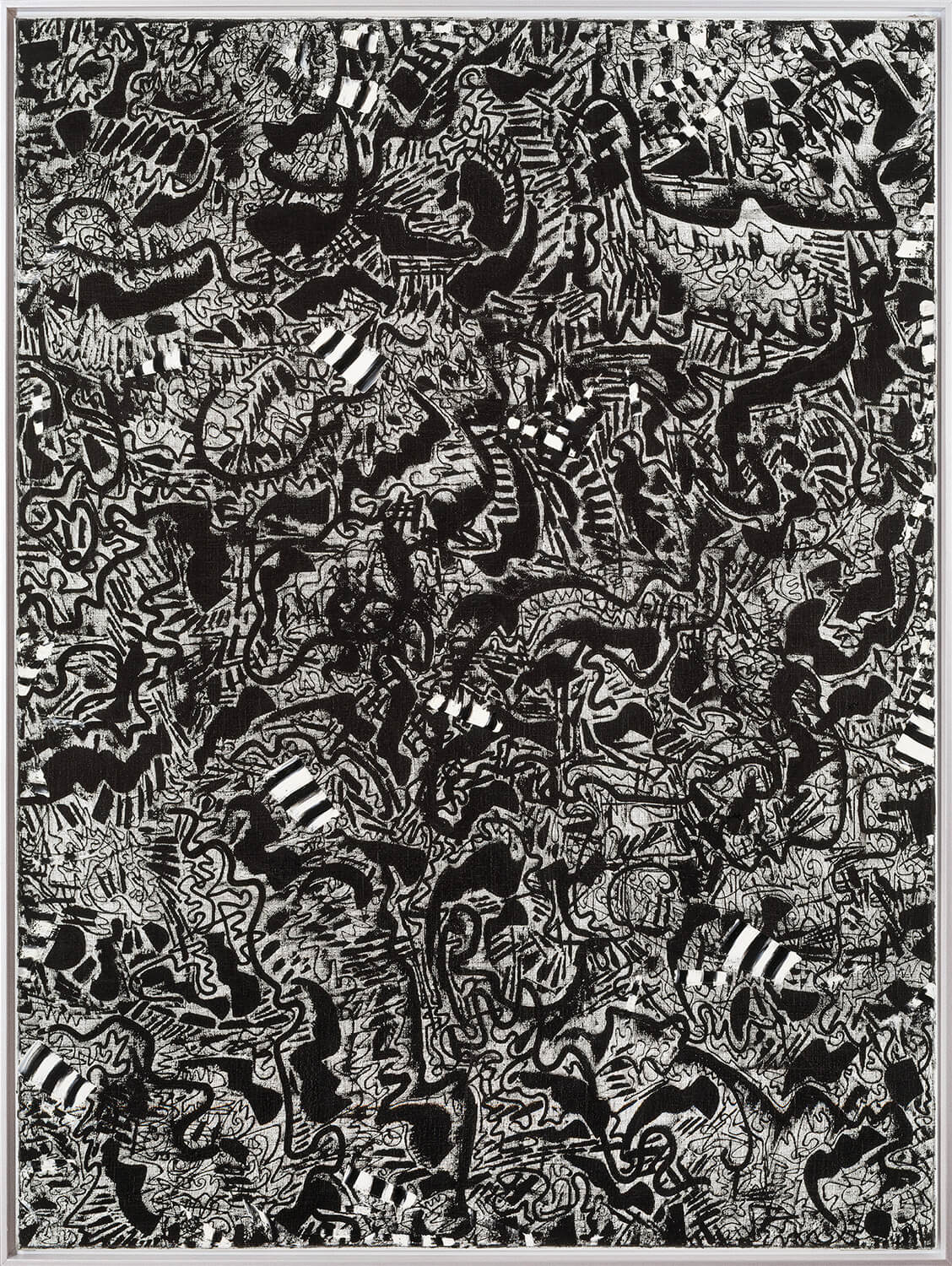

Evgeny Chubarov.

Untitled, 1996

Untitled, 1996

The Miracle of St. George and The Dragon. Last quarter–end 15th century. Middle Rus' (Rostov)

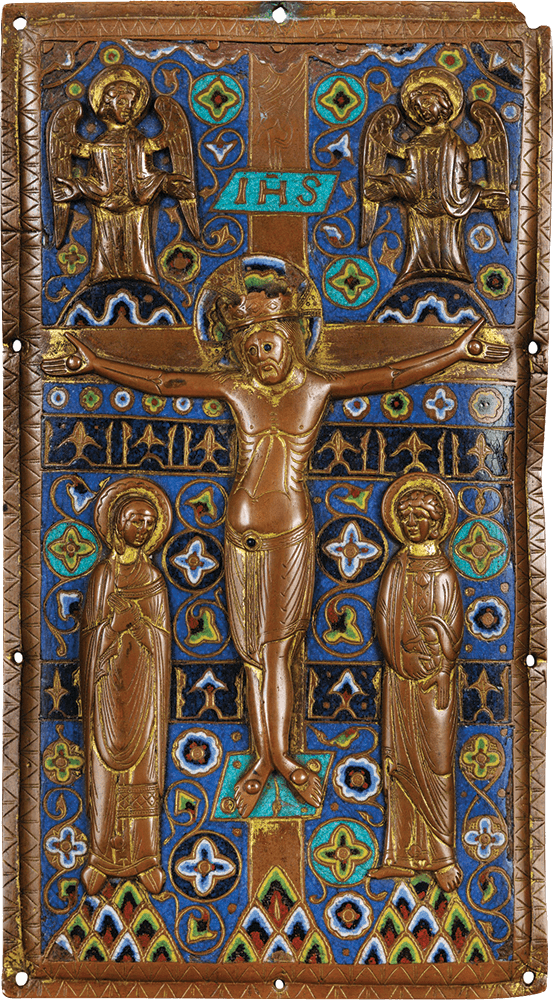

The Processional Cross. Limoges, Circa 1230–1250

The House of Spirit collection comprises over 100 meticulously chosen artifacts of immense historical and artistic value. These works collectively embody the evolution of religious painting with a distinct Byzantine influence, encapsulating the diverse realms of the applied arts from Syria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, Russia, Greece, France, and other countries:

• Over 20 illuminated Armenian and Islamic manuscripts (12–17th centuries)

• Over 60 rare Orthodox icons (14–16th centuries)

• Over 20 abstract paintings by Armenian born artist Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012)

• Selected group of Limoges Enameled Crosses and Manuscript covers (11–17th centuries) of Christian traditions of the Medieval Europe.

An important and unique collection, expertly assembled over three decades, forms the basis of a comprehensive museum gathering. Each artefact comes from the world's most respected private and museum collections, accompanied by professional expertise and indisputable proof of provenance, including the exhibitions in the leading museum institutions worldwide, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; The Central Andrey Rublev Museum of Ancient Russian Culture and Art, Moscow; The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; The St. Louis Art Museum; Haus der Kunst, Munich; The Gothenburg Museum of Art, Gothenburg; The National Gallery, Oslo; Oslo Kunstforening, Oslo; The Archbishop's Palace Museum, Trondheim and many others.

• Over 20 illuminated Armenian and Islamic manuscripts (12–17th centuries)

• Over 60 rare Orthodox icons (14–16th centuries)

• Over 20 abstract paintings by Armenian born artist Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012)

• Selected group of Limoges Enameled Crosses and Manuscript covers (11–17th centuries) of Christian traditions of the Medieval Europe.

An important and unique collection, expertly assembled over three decades, forms the basis of a comprehensive museum gathering. Each artefact comes from the world's most respected private and museum collections, accompanied by professional expertise and indisputable proof of provenance, including the exhibitions in the leading museum institutions worldwide, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; The Central Andrey Rublev Museum of Ancient Russian Culture and Art, Moscow; The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; The St. Louis Art Museum; Haus der Kunst, Munich; The Gothenburg Museum of Art, Gothenburg; The National Gallery, Oslo; Oslo Kunstforening, Oslo; The Archbishop's Palace Museum, Trondheim and many others.

The House of Spirit collection comprises over 100 meticulously chosen artifacts of immense historical and artistic value. These works collectively embody the evolution of religious painting with a distinct Byzantine influence, encapsulating the diverse realms of the applied arts from Syria, Armenia, Iran, Turkey, Russia, Greece, France, and other countries:

• Over 20 illuminated Armenian and Islamic manuscripts (12–17th centuries)

• Over 60 rare Orthodox icons (14–16th centuries)

• Over 20 abstract paintings by Armenian born artist Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012)

• Selected group of Limoges Enameled Crosses and Manuscript covers (11–17th centuries) of Christian traditions of the Medieval Europe.

An important and unique collection, expertly assembled over three decades, forms the basis of a comprehensive museum gathering. Each artefact comes from the world's most respected private and museum collections, accompanied by professional expertise and indisputable proof of provenance, including the exhibitions in the leading museum institutions worldwide, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; The Central Andrey Rublev Museum of Ancient Russian Culture and Art, Moscow; The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; The St. Louis Art Museum; Haus der Kunst, Munich; The Gothenburg Museum of Art, Gothenburg; The National Gallery, Oslo; Oslo Kunstforening, Oslo; The Archbishop's Palace Museum, Trondheim and many others.

• Over 20 illuminated Armenian and Islamic manuscripts (12–17th centuries)

• Over 60 rare Orthodox icons (14–16th centuries)

• Over 20 abstract paintings by Armenian born artist Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012)

• Selected group of Limoges Enameled Crosses and Manuscript covers (11–17th centuries) of Christian traditions of the Medieval Europe.

An important and unique collection, expertly assembled over three decades, forms the basis of a comprehensive museum gathering. Each artefact comes from the world's most respected private and museum collections, accompanied by professional expertise and indisputable proof of provenance, including the exhibitions in the leading museum institutions worldwide, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh; The Central Andrey Rublev Museum of Ancient Russian Culture and Art, Moscow; The State Russian Museum, St. Petersburg; The St. Louis Art Museum; Haus der Kunst, Munich; The Gothenburg Museum of Art, Gothenburg; The National Gallery, Oslo; Oslo Kunstforening, Oslo; The Archbishop's Palace Museum, Trondheim and many others.

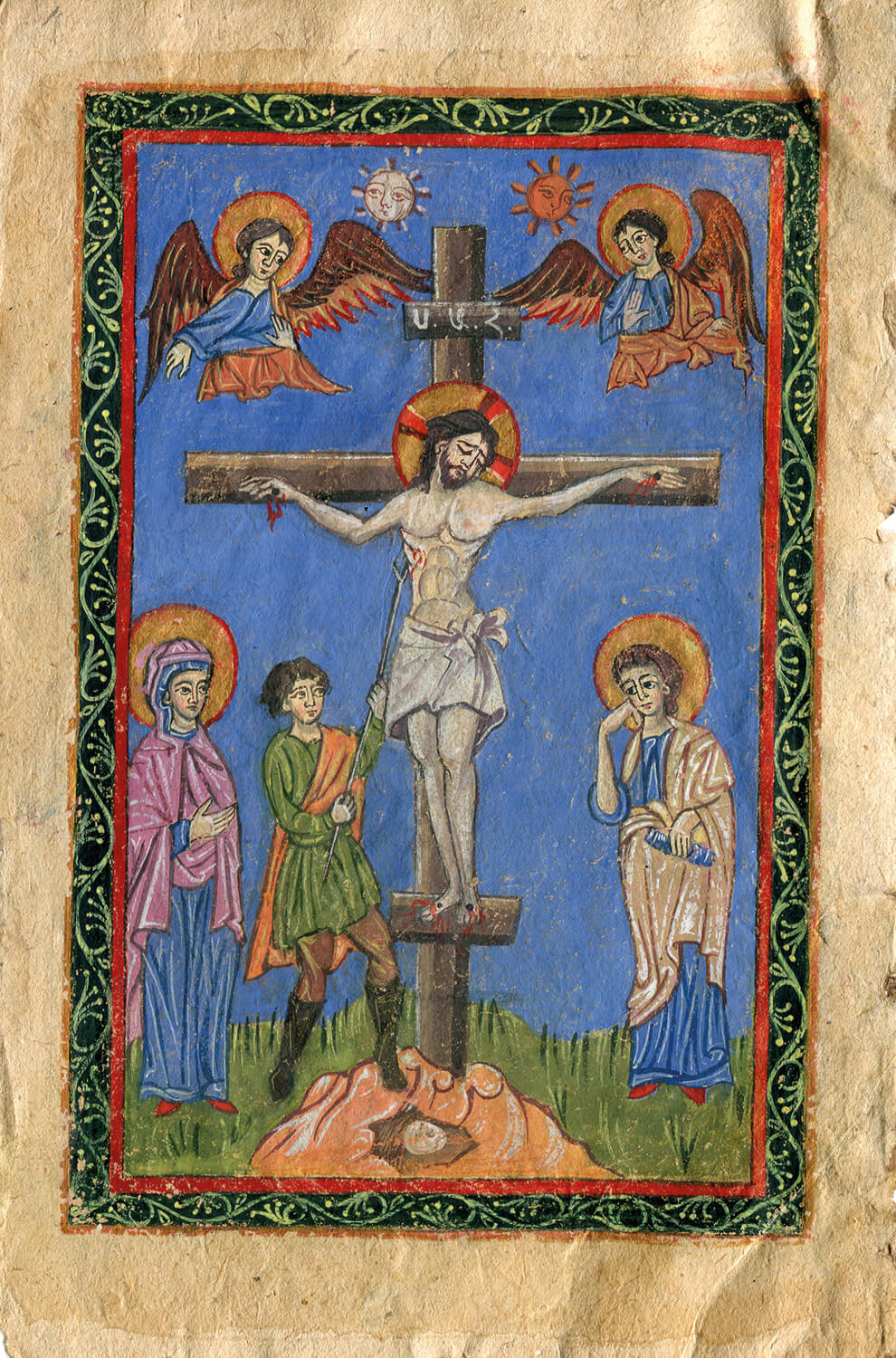

XIV–XVI CENTURY ICONS

The collection comprises over 60 rare Orthodox icons (14–16th centuries)

Selected examples from The House of Spirit Collection

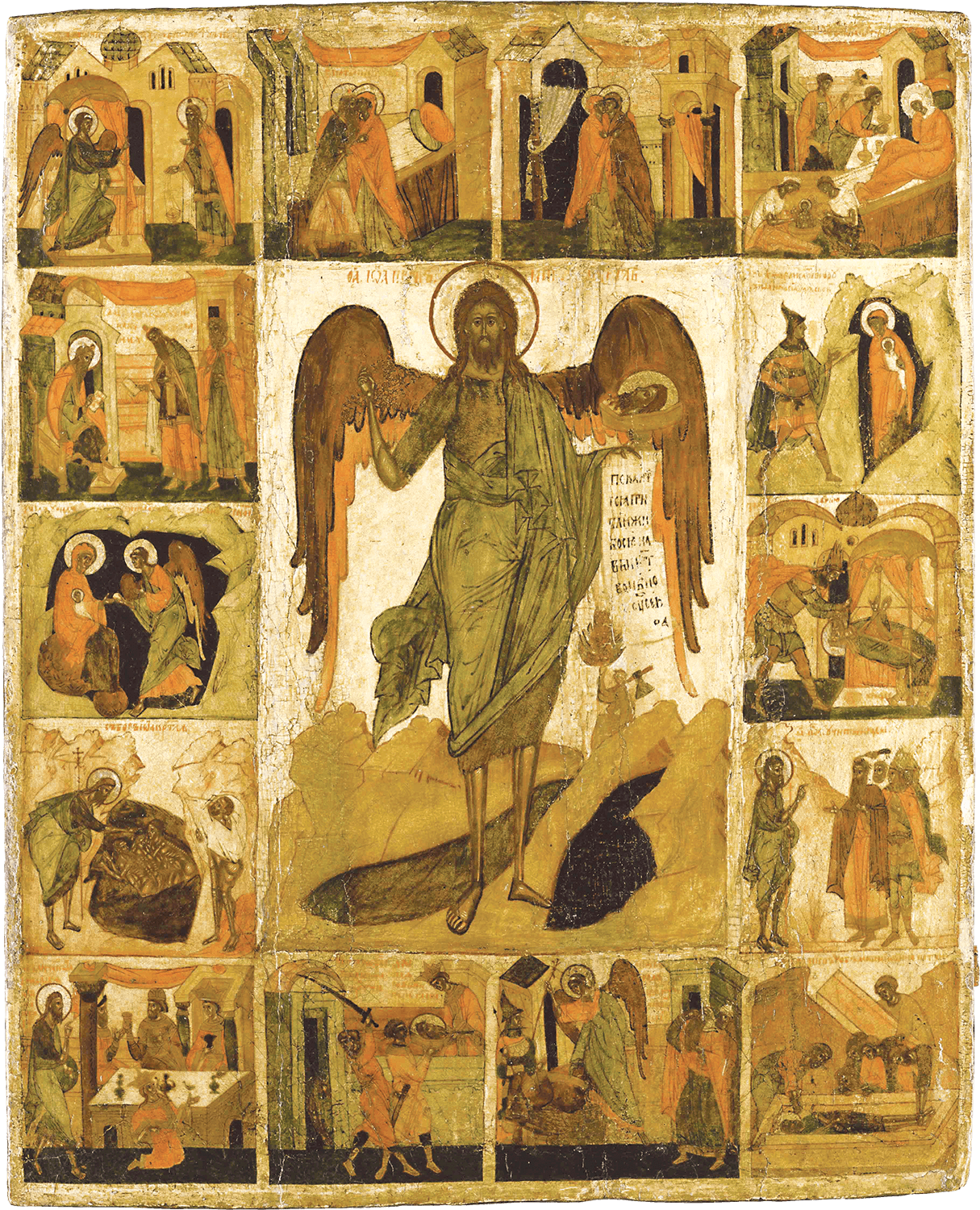

1. John The Baptist, Angel of The Desert, with 14 Scenes from his life. Last quarter 15th century, Middle Rus'

2. An icon of the Hodigitria Mother of God. Circa 1500, Crete, circle of Andreas Ritzos

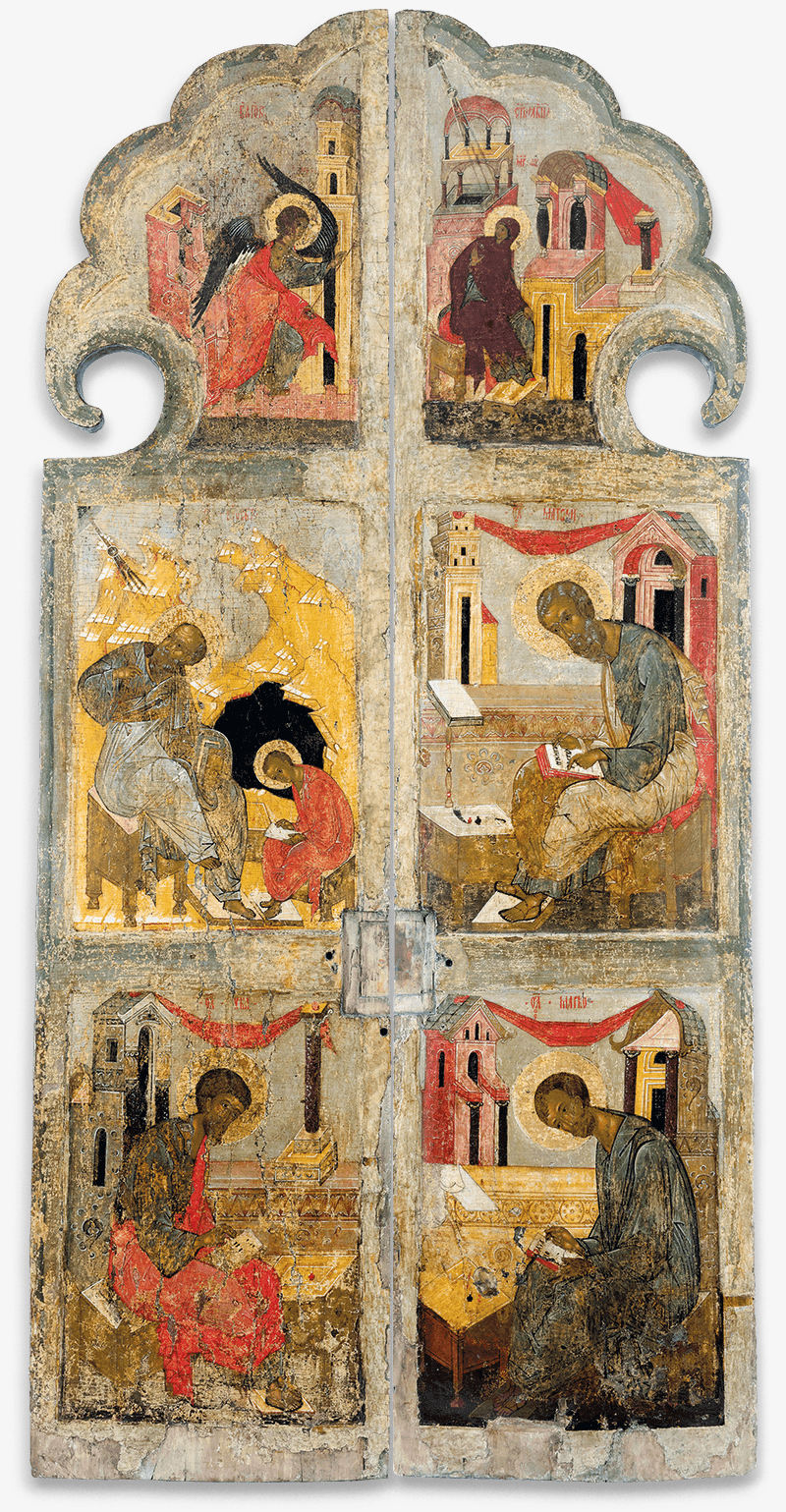

3. Royal Doors of The Annunciation and The Evangelists, 1410–20s. Andrey Rublev (?) or his closest associates. Moscow School

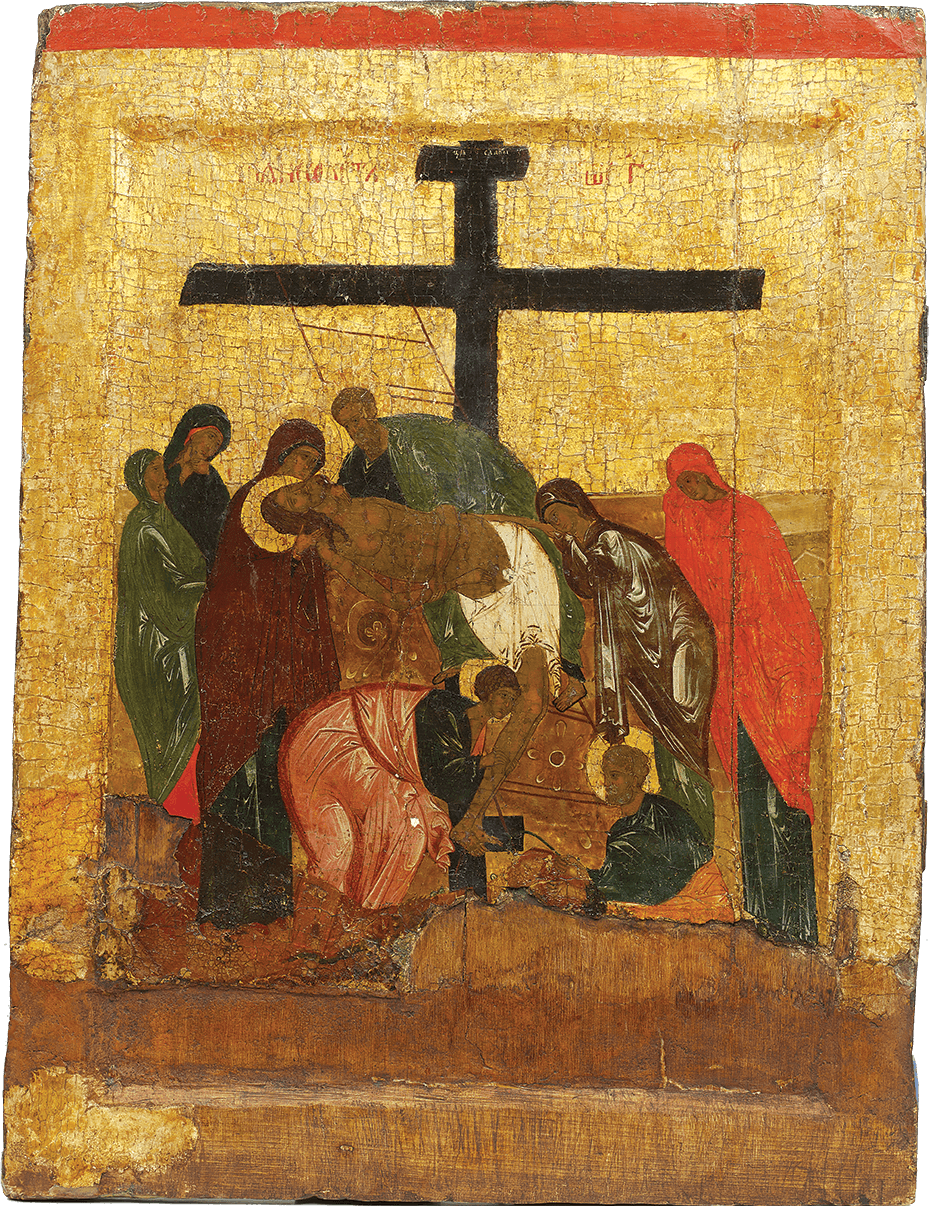

4. The Descent from The Cross, Icon from The Fiests Tier of Iconostasis. End 15th Century. Middle Rus'

1. John The Baptist, Angel of The Desert, with 14 Scenes from his life. Last quarter 15th century, Middle Rus'

2. An icon of the Hodigitria Mother of God. Circa 1500, Crete, circle of Andreas Ritzos

3. Royal Doors of The Annunciation and The Evangelists, 1410–20s. Andrey Rublev (?) or his closest associates. Moscow School

4. The Descent from The Cross, Icon from The Fiests Tier of Iconostasis. End 15th Century. Middle Rus'

1

2

3

4

The Orthodox icon is a prime example of Christian religious painting in medieval Eastern Europe, which reached its heyday in the 14th and 15th centuries, featuring distinguished masters such as Andrey Rublev, Feofan the Greek, and Dionysius. This art form exists on the chronological borderline of Byzantine history, effectively combining the highest standards of Byzantine art with a distinct national specificity. It formulates a lofty ideal that encapsulates the spiritual experience of the classical Orthodox Middle Ages.

With the expansion of Christianity, the icon has become a widely recognized and revered object found in various corners of the world.

The subjects and iconography depicted in these icons convey stories that are shared among different confessions, thereby serving as a bridge in cultural and historical conversations.

With the expansion of Christianity, the icon has become a widely recognized and revered object found in various corners of the world.

The subjects and iconography depicted in these icons convey stories that are shared among different confessions, thereby serving as a bridge in cultural and historical conversations.

The Orthodox icon is a prime example of Christian religious painting in medieval Eastern Europe, which reached its heyday in the 14th and 15th centuries, featuring distinguished masters such as Andrey Rublev, Feofan the Greek, and Dionysius. This art form exists on the chronological borderline of Byzantine history, effectively combining the highest standards of Byzantine art with a distinct national specificity. It formulates a lofty ideal that encapsulates the spiritual experience of the classical Orthodox Middle Ages.

With the expansion of Christianity, the icon has become a widely recognized and revered object found in various corners of the world.

The subjects and iconography depicted in these icons convey stories that are shared among different confessions, thereby serving as a bridge in cultural and historical conversations.

With the expansion of Christianity, the icon has become a widely recognized and revered object found in various corners of the world.

The subjects and iconography depicted in these icons convey stories that are shared among different confessions, thereby serving as a bridge in cultural and historical conversations.

Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1996

Resurrection – The Descent To Hell. 1470–1480s, Novgorod

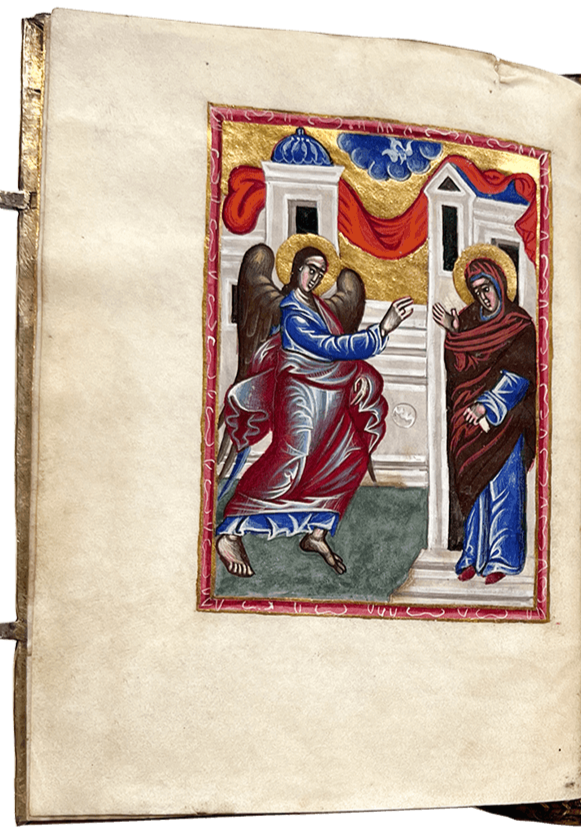

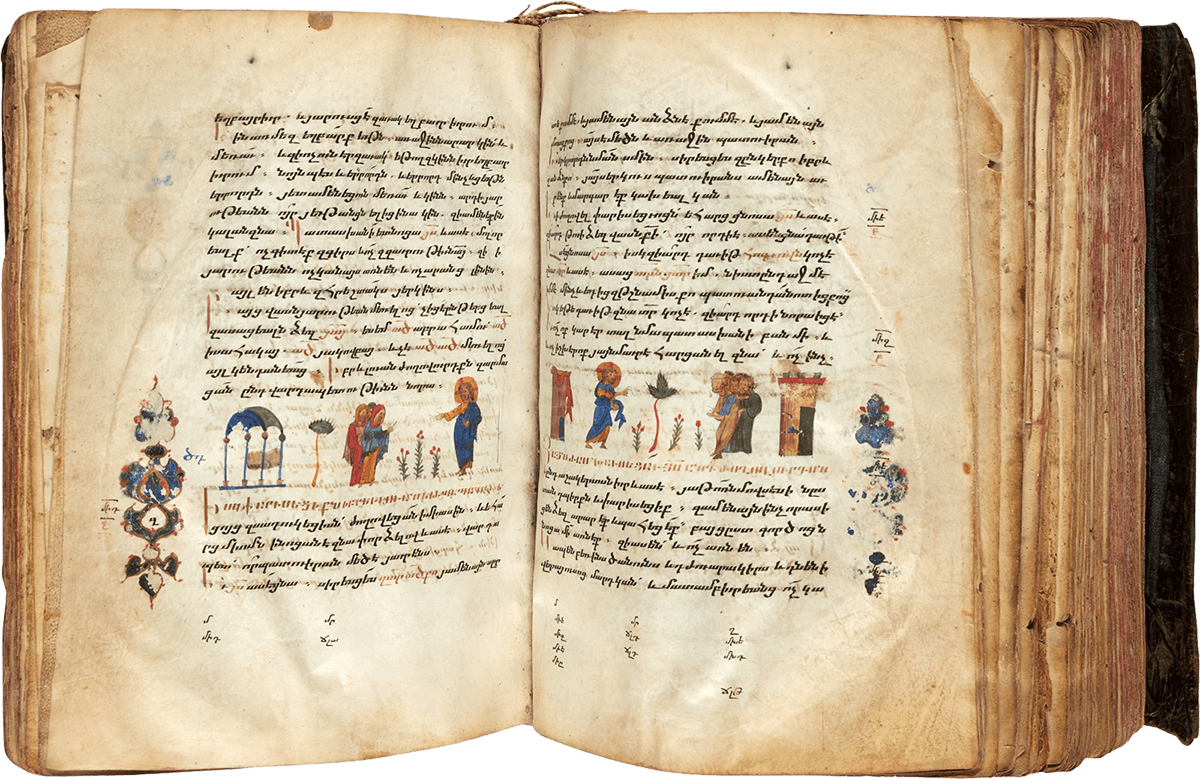

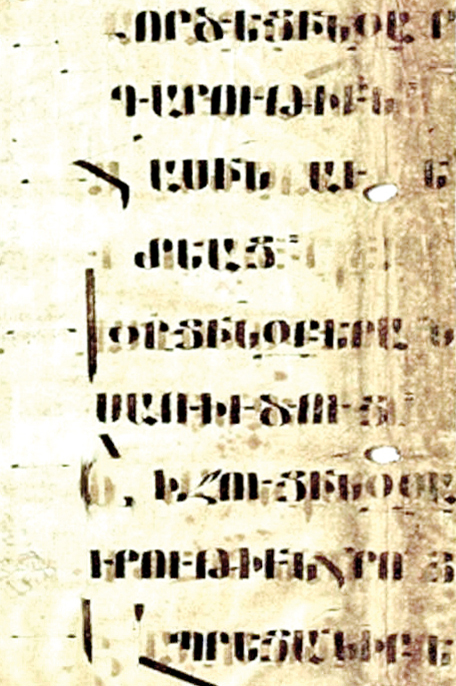

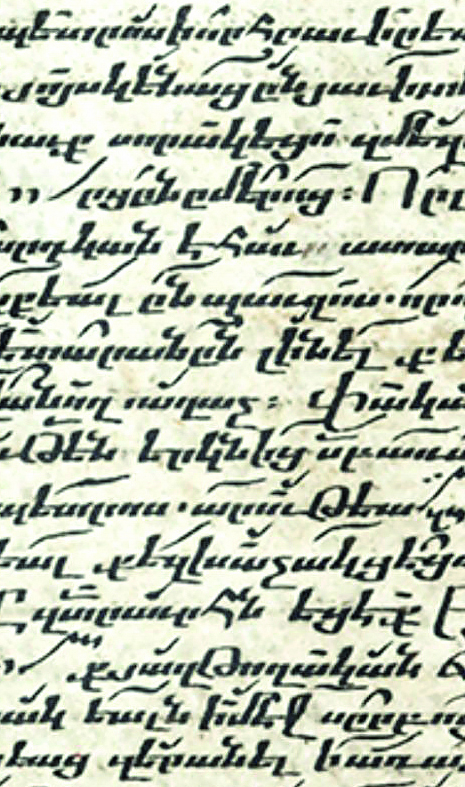

XI–XVII CENTURY MANUSCRIPTS

The collection comprises over 20 illuminated Armenian and Islamic manuscripts (12–17th centuries)

Selected examples from The House of Spirit Collection

1. John The Baptist, Angel of The Desert, with 14 Scenes from his life. Last quarter 15th century, Middle Rus'

2. An icon of the Hodigitria Mother of God. Circa 1500, Crete, circle of Andreas Ritzos

3. Royal Doors of The Annunciation and The Evangelists, 1410–20s. Andrey Rublev (?) or his closest associates. Moscow School

4. The Descent from The Cross, Icon from The Fiests Tier of Iconostasis. End 15th Century. Middle Rus'

1. John The Baptist, Angel of The Desert, with 14 Scenes from his life. Last quarter 15th century, Middle Rus'

2. An icon of the Hodigitria Mother of God. Circa 1500, Crete, circle of Andreas Ritzos

3. Royal Doors of The Annunciation and The Evangelists, 1410–20s. Andrey Rublev (?) or his closest associates. Moscow School

4. The Descent from The Cross, Icon from The Fiests Tier of Iconostasis. End 15th Century. Middle Rus'

1

2

3

4

Armenian illuminated manuscripts are some of the most lavishly decorated codices of the Christian churches from the Middle East. They constitute an incredibly significant cultural heritage and showcase the vitality and creativity of a culture that interacted with the Latin West, Byzantium, and the Iranian world. This cultural exchange allowed them to draw inspiration from classical antiquity and ultimately produce their own magnificent treasures.

The Gospels hold a paramount position among these manuscripts, primarily due to the Armenian community's profound reverence for the sacred texts. They are esteemed in a manner similar to how Greek and Russian Christians hold holy icons in high regard. Armenian rulers often carried these texts into battle, and individual copies of the Gospels were assigned sacred names, believed to possess miraculous powers. For the Armenians, a manuscript book carries far more significance than being a mere tool of transmission. It holds a dual value in Armenian eyes: it preserves and disseminates the texts it contains, but it also possesses intrinsic value as a manuscript book—an object that has become a symbol of their culture and identity.

The Gospels hold a paramount position among these manuscripts, primarily due to the Armenian community's profound reverence for the sacred texts. They are esteemed in a manner similar to how Greek and Russian Christians hold holy icons in high regard. Armenian rulers often carried these texts into battle, and individual copies of the Gospels were assigned sacred names, believed to possess miraculous powers. For the Armenians, a manuscript book carries far more significance than being a mere tool of transmission. It holds a dual value in Armenian eyes: it preserves and disseminates the texts it contains, but it also possesses intrinsic value as a manuscript book—an object that has become a symbol of their culture and identity.

Armenian illuminated manuscripts are some of the most lavishly decorated codices of the Christian churches from the Middle East. They constitute an incredibly significant cultural heritage and showcase the vitality and creativity of a culture that interacted with the Latin West, Byzantium, and the Iranian world. This cultural exchange allowed them to draw inspiration from classical antiquity and ultimately produce their own magnificent treasures.

The Gospels hold a paramount position among these manuscripts, primarily due to the Armenian community's profound reverence for the sacred texts. They are esteemed in a manner similar to how Greek and Russian Christians hold holy icons in high regard. Armenian rulers often carried these texts into battle, and individual copies of the Gospels were assigned sacred names, believed to possess miraculous powers. For the Armenians, a manuscript book carries far more significance than being a mere tool of transmission. It holds a dual value in Armenian eyes: it preserves and disseminates the texts it contains, but it also possesses intrinsic value as a manuscript book—an object that has become a symbol of their culture and identity.

The Gospels hold a paramount position among these manuscripts, primarily due to the Armenian community's profound reverence for the sacred texts. They are esteemed in a manner similar to how Greek and Russian Christians hold holy icons in high regard. Armenian rulers often carried these texts into battle, and individual copies of the Gospels were assigned sacred names, believed to possess miraculous powers. For the Armenians, a manuscript book carries far more significance than being a mere tool of transmission. It holds a dual value in Armenian eyes: it preserves and disseminates the texts it contains, but it also possesses intrinsic value as a manuscript book—an object that has become a symbol of their culture and identity.

Evgeny Chubarov.

Untitled, 1996

Untitled, 1996

Armenian manuscript.

5th–6th century

5th–6th century

Armenian manuscript.

15th century

15th century

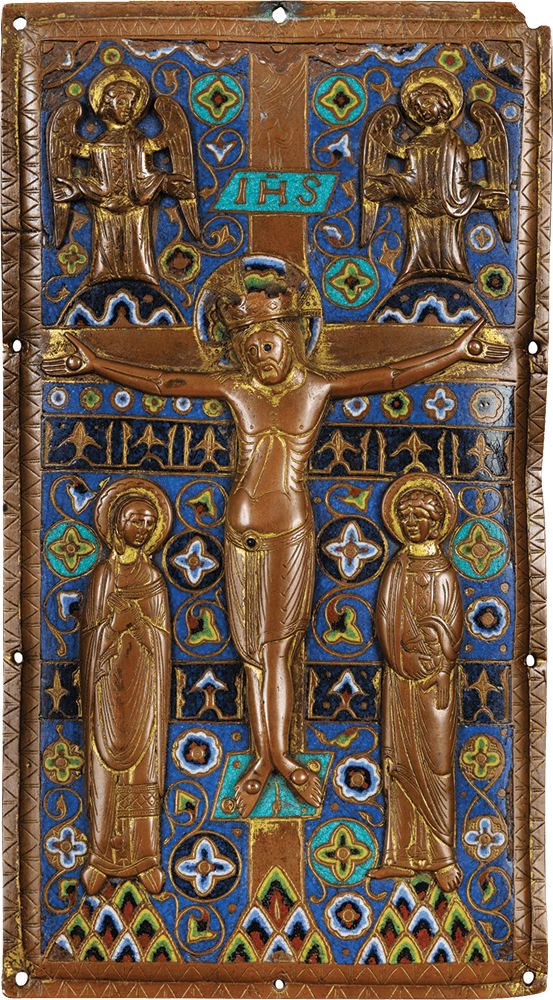

LIMOGES CRUCIFIXES (XIII CENTURY)

The collection comprises selected group of Limoges Enameled Crosses and Manuscript covers (11–17th centuries) of Christian traditions of the Medieval Europe.

Selected examples from The House of Spirit Collection

1. Champlevé Enamel Bookcover with The Crucifixion. Circa 1210–30s, Limoges, France

2. Champlevé Enamel Book Cover Showing The Crucifixion. First quarter 13th century, Limoges, France

3. A Limoges Champlevé Enamel Gilt Copper Processional Cross. First half 13th century, Limoges, France

4. Processional Cross. First half 13th century and later. Limoges, France

1. Champlevé Enamel Bookcover with The Crucifixion. Circa 1210–30s, Limoges, France

2. Champlevé Enamel Book Cover Showing The Crucifixion. First quarter 13th century, Limoges, France

3. A Limoges Champlevé Enamel Gilt Copper Processional Cross. First half 13th century, Limoges, France

4. Processional Cross. First half 13th century and later. Limoges, France

1

2

3

4

The technique known as champlevé was perfected in the French city of Limoges. It was first recorded in the 13th century BC in Cyprus, and later spread through ancient Greece into Europe, where it was extensively used by the Celts in Gaul and Britain. From the 6th century onwards, Byzantine jewelers perfected the cloisonné enamelling technique, which involved dropping colored glass into shapes created by soldered strips of gold. This skill was carried by the Ostrogoths into Italy and by Visigoths to the Iberian Peninsula.

During the first half of the 12th century, three distinct centers emerged in Northern Europe: the Meuse Valley, Cologne, and Limoges. These centers elevated the art of enamelling to new heights. For Western Christendom, enamelling techniques not only offered vibrantly colored splendor for the many liturgical objects found in churches and treasuries, but the process itself was seen as symbolic of the transformation of Christian souls through purgatorial fire.

Under the patronage of local abbeys, craftsmen around Limoges began perfecting the champlevé technique of enamelling during the first half of the 12th century. By 1170, Limoges enamels had gained widespread acclaim throughout Europe. Workshops sprang up around a large abbey located on the pilgrims' trail to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Limoges enamels were often used to decorate reliquaries, as saintly relics were highly popular during that time. In 1215, Pope Innocent III decreed that every church in Europe must own at least one Limoges enamel.

During the first half of the 12th century, three distinct centers emerged in Northern Europe: the Meuse Valley, Cologne, and Limoges. These centers elevated the art of enamelling to new heights. For Western Christendom, enamelling techniques not only offered vibrantly colored splendor for the many liturgical objects found in churches and treasuries, but the process itself was seen as symbolic of the transformation of Christian souls through purgatorial fire.

Under the patronage of local abbeys, craftsmen around Limoges began perfecting the champlevé technique of enamelling during the first half of the 12th century. By 1170, Limoges enamels had gained widespread acclaim throughout Europe. Workshops sprang up around a large abbey located on the pilgrims' trail to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Limoges enamels were often used to decorate reliquaries, as saintly relics were highly popular during that time. In 1215, Pope Innocent III decreed that every church in Europe must own at least one Limoges enamel.

The technique known as champlevé was perfected in the French city of Limoges. It was first recorded in the 13th century BC in Cyprus, and later spread through ancient Greece into Europe, where it was extensively used by the Celts in Gaul and Britain. From the 6th century onwards, Byzantine jewelers perfected the cloisonné enamelling technique, which involved dropping colored glass into shapes created by soldered strips of gold. This skill was carried by the Ostrogoths into Italy and by Visigoths to the Iberian Peninsula.

During the first half of the 12th century, three distinct centers emerged in Northern Europe: the Meuse Valley, Cologne, and Limoges. These centers elevated the art of enamelling to new heights. For Western Christendom, enamelling techniques not only offered vibrantly colored splendor for the many liturgical objects found in churches and treasuries, but the process itself was seen as symbolic of the transformation of Christian souls through purgatorial fire.

Under the patronage of local abbeys, craftsmen around Limoges began perfecting the champlevé technique of enamelling during the first half of the 12th century. By 1170, Limoges enamels had gained widespread acclaim throughout Europe. Workshops sprang up around a large abbey located on the pilgrims' trail to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Limoges enamels were often used to decorate reliquaries, as saintly relics were highly popular during that time. In 1215, Pope Innocent III decreed that every church in Europe must own at least one Limoges enamel.

During the first half of the 12th century, three distinct centers emerged in Northern Europe: the Meuse Valley, Cologne, and Limoges. These centers elevated the art of enamelling to new heights. For Western Christendom, enamelling techniques not only offered vibrantly colored splendor for the many liturgical objects found in churches and treasuries, but the process itself was seen as symbolic of the transformation of Christian souls through purgatorial fire.

Under the patronage of local abbeys, craftsmen around Limoges began perfecting the champlevé technique of enamelling during the first half of the 12th century. By 1170, Limoges enamels had gained widespread acclaim throughout Europe. Workshops sprang up around a large abbey located on the pilgrims' trail to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Limoges enamels were often used to decorate reliquaries, as saintly relics were highly popular during that time. In 1215, Pope Innocent III decreed that every church in Europe must own at least one Limoges enamel.

Armenian Manuscript (detail),

14th century

14th century

Champlevé Enamel Bookcover with The Crucifixion Circa 1210–30s, Limoges, France

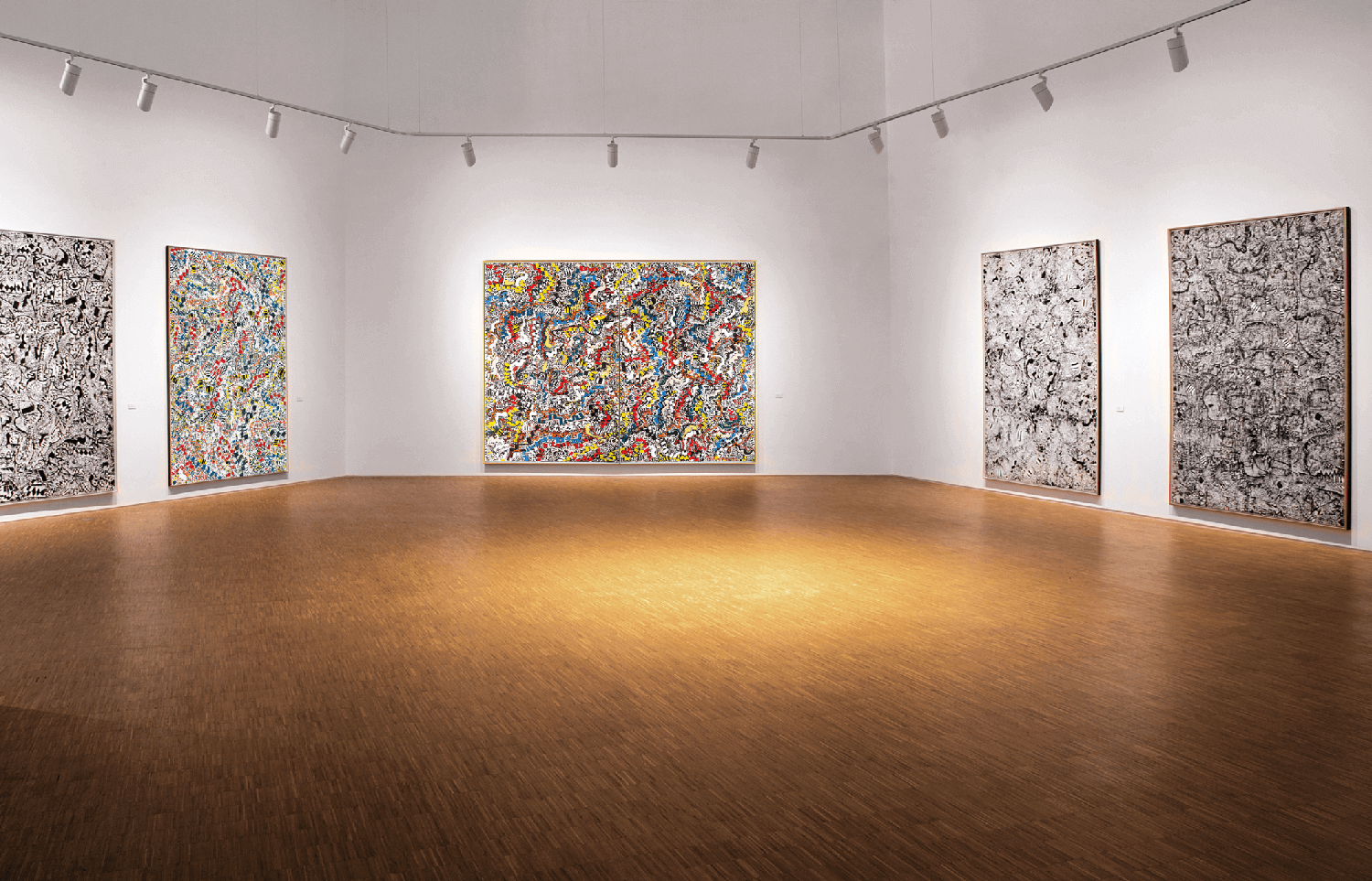

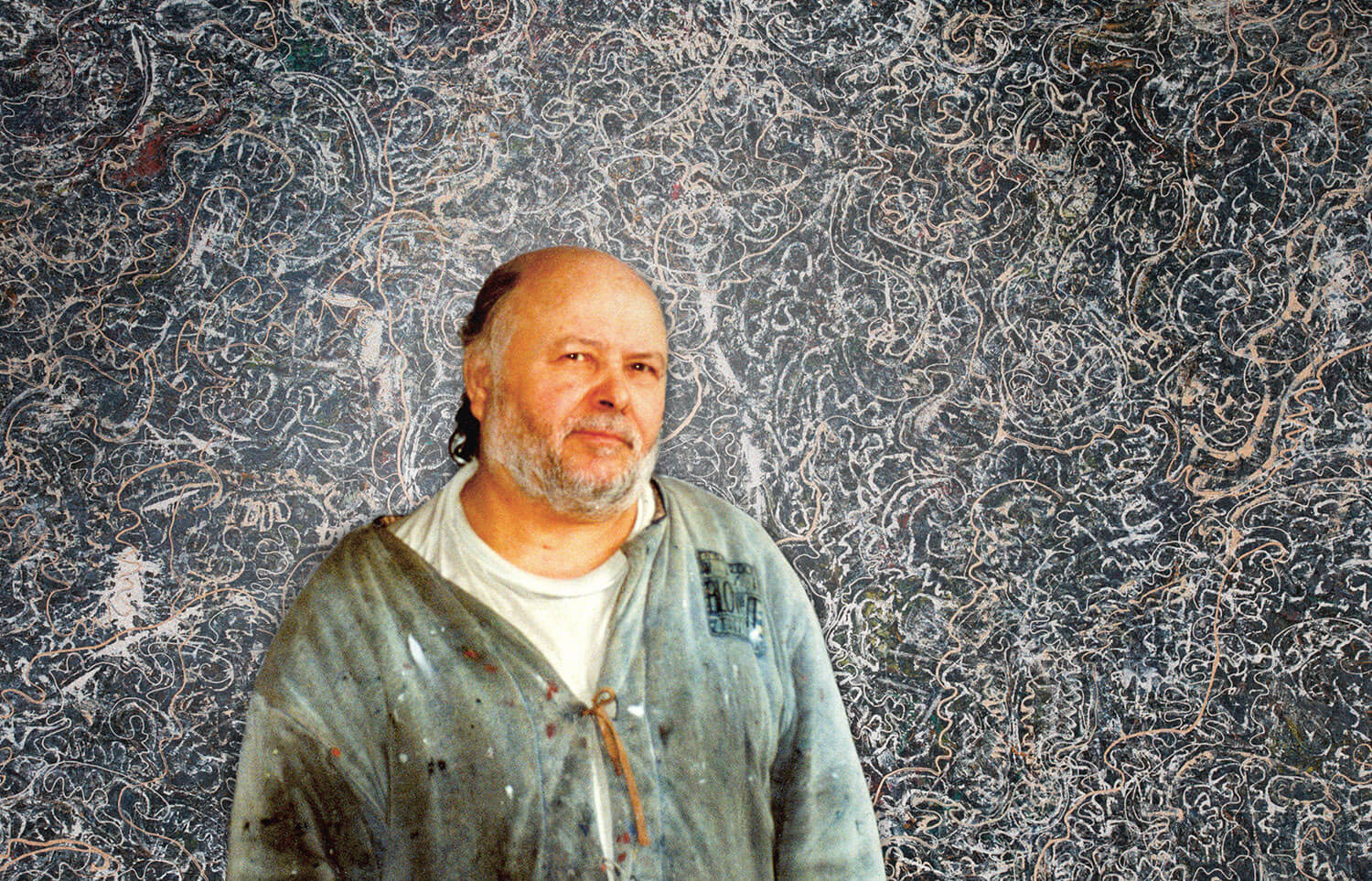

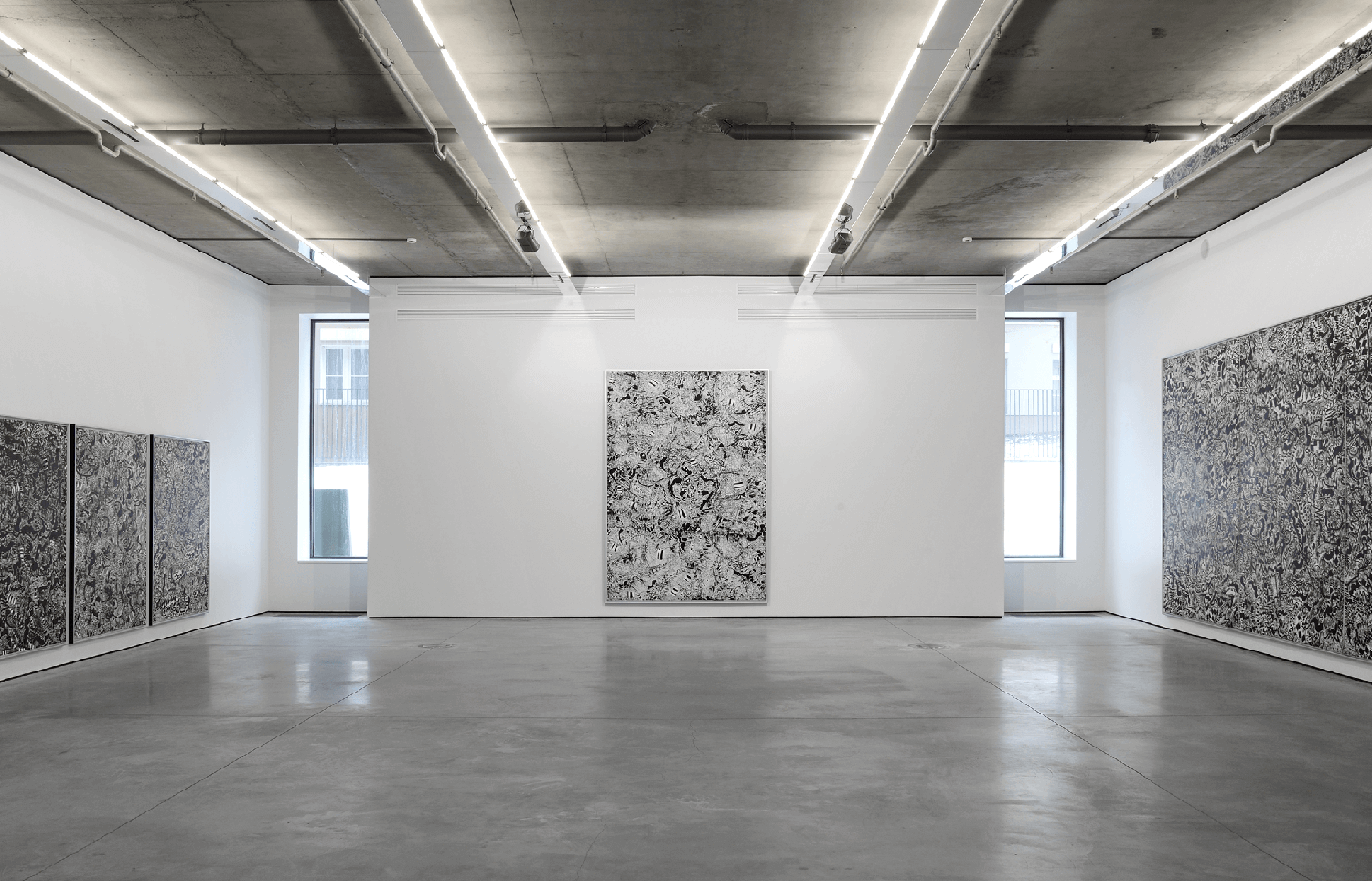

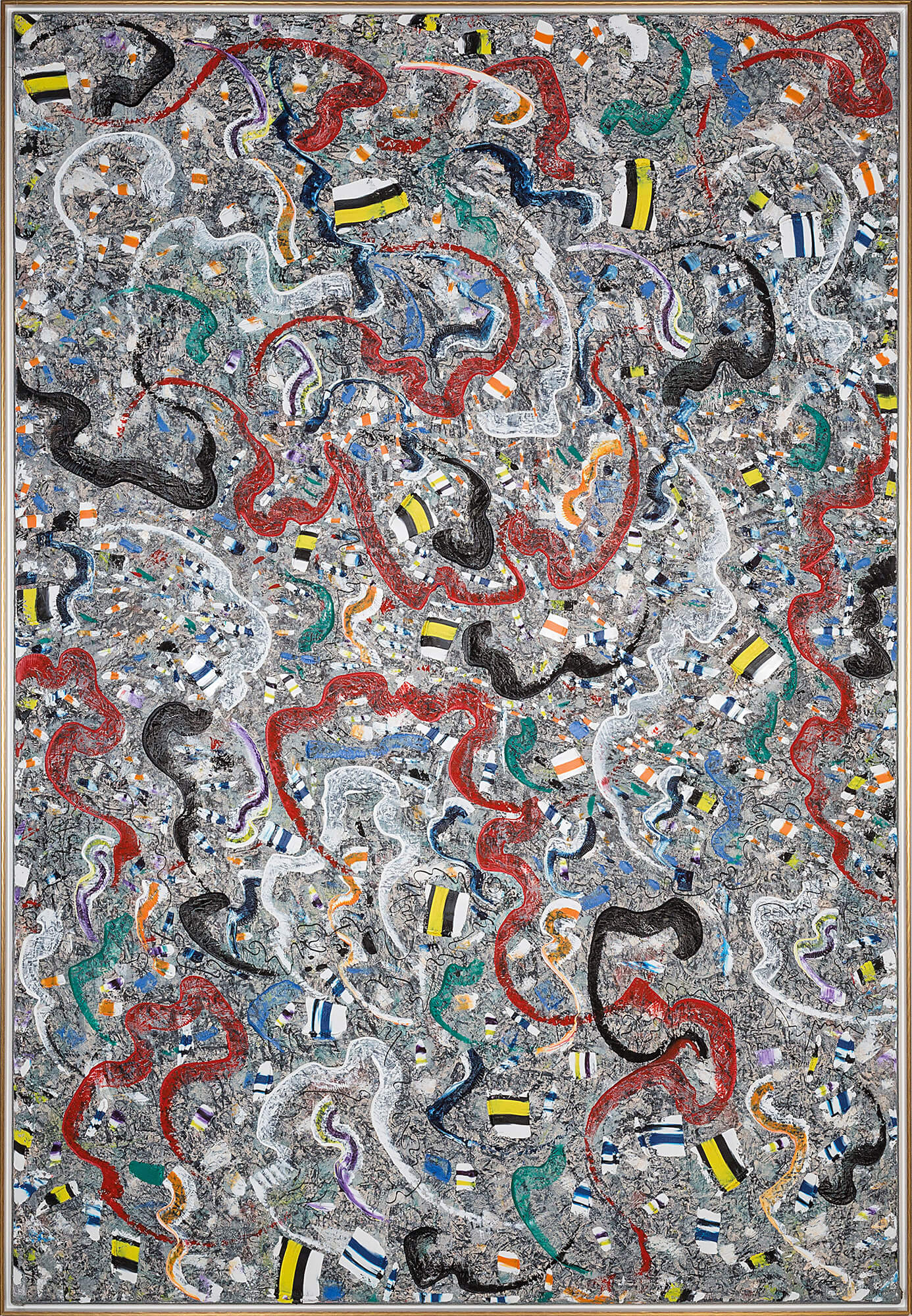

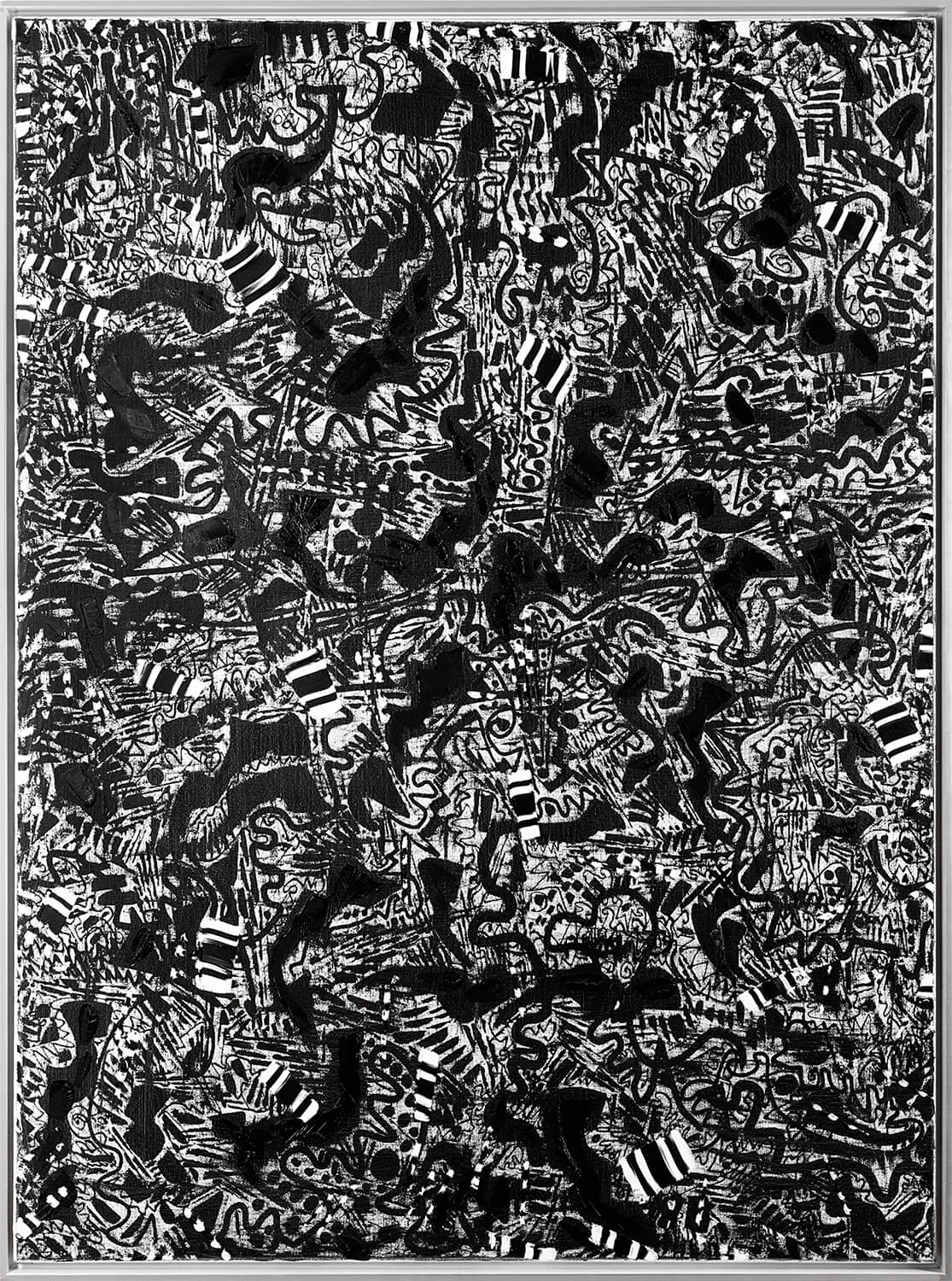

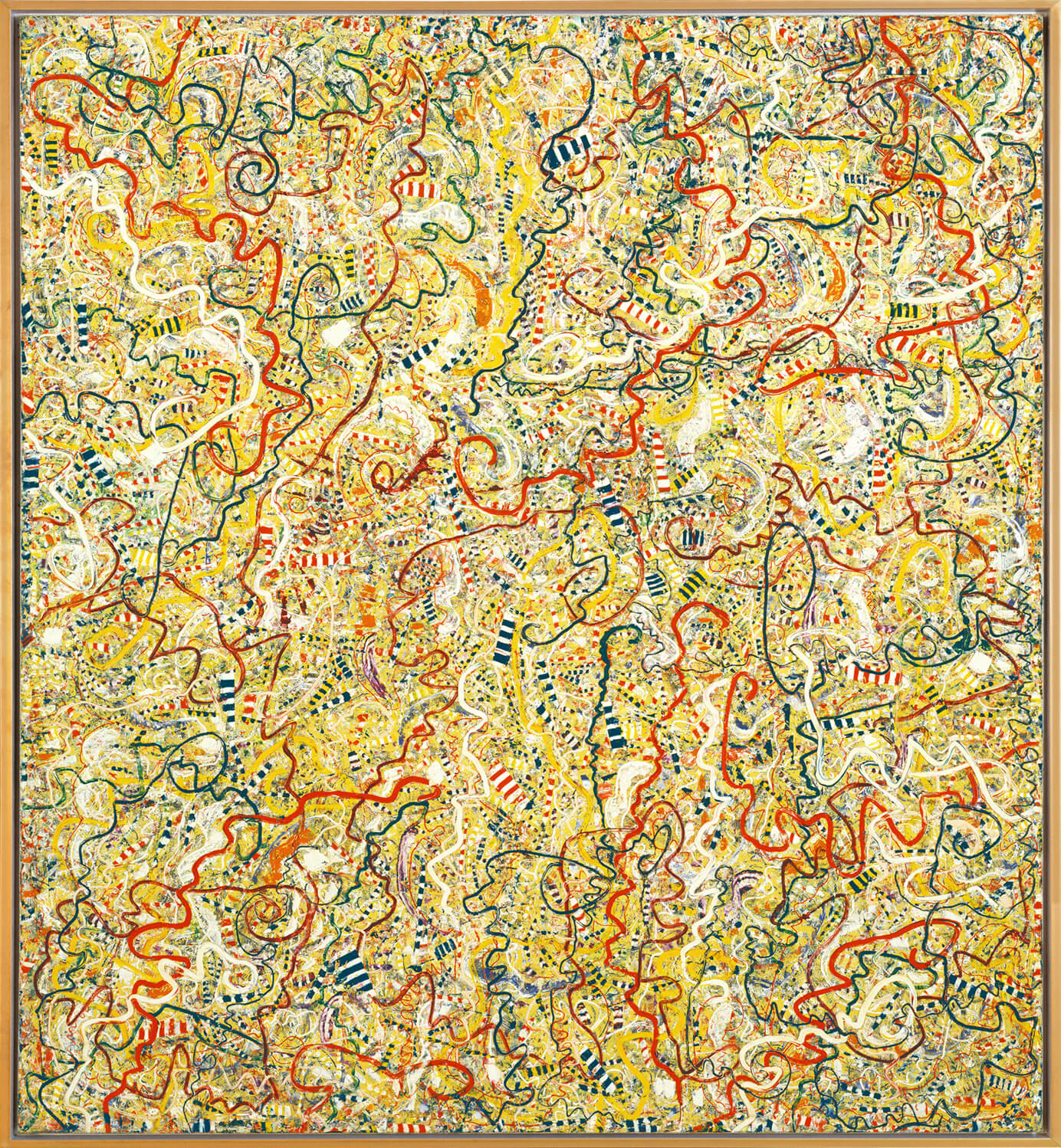

EVGENY CHUBAROV

The collection comprises over 20 abstract paintings by Armenian born artist Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012)

Selected examples from The House of Spirit Collection

1. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1995 (290 x 200 cm)

2. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1995 (300 x 200 cm)

3. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1992-1993 (206 x 189 cm)

4. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1996 (200 x 150 cm)

1. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1995 (290 x 200 cm)

2. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1995 (300 x 200 cm)

3. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1992-1993 (206 x 189 cm)

4. Evgeny Chubarov. Untitled, 1996 (200 x 150 cm)

1

2

3

4

The power of visual mediation lies in its ability to represent space, embody ideas, and navigate the realm between figuration and abstraction. It evokes emotions and establishes a profound connection with the viewer. This essence is central to the artistic work of Evgeny Chubarov.

Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012), an artist of Armenian origin, drew deep inspiration from the history of Medieval relics such as Christian Icons and Armenian Manuscripts, which always surrounded him in his studio. Rooted in the rich ongoing dialogue between the East and West, his abstract works fuse the aesthetics of ancient calligraphy and Byzantine art with contemporary painting.

Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012), an artist of Armenian origin, drew deep inspiration from the history of Medieval relics such as Christian Icons and Armenian Manuscripts, which always surrounded him in his studio. Rooted in the rich ongoing dialogue between the East and West, his abstract works fuse the aesthetics of ancient calligraphy and Byzantine art with contemporary painting.

The power of visual mediation lies in its ability to represent space, embody ideas, and navigate the realm between figuration and abstraction. It evokes emotions and establishes a profound connection with the viewer. This essence is central to the artistic work of Evgeny Chubarov.

Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012), an artist of Armenian origin, drew deep inspiration from the history of Medieval relics such as Christian Icons and Armenian Manuscripts, which always surrounded him in his studio. Rooted in the rich ongoing dialogue between the East and West, his abstract works fuse the aesthetics of ancient calligraphy and Byzantine art with contemporary painting.

Evgeny Chubarov (1934–2012), an artist of Armenian origin, drew deep inspiration from the history of Medieval relics such as Christian Icons and Armenian Manuscripts, which always surrounded him in his studio. Rooted in the rich ongoing dialogue between the East and West, his abstract works fuse the aesthetics of ancient calligraphy and Byzantine art with contemporary painting.